We live in a world with many labels for gender and sexual identities. But where did they come from? Some of them originate in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when people, a lot of them scientists or medical doctors, invented a wide range of new labels and categories. The second workshop of the ‘Transformations’ series explored the history of labels for gender and sexuality – looking at who created them, who has used them, and why.

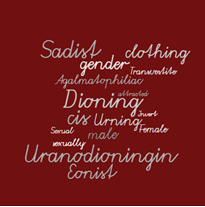

We began by exploring the wide range of new terms created in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and attempted to match them with their definitions. You can try it yourself here! These categories and labels were invented by medically trained doctors such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis, but also people like Karl Heinrich Ulrichs who coined, and himself identified with, the term “urning” (a person assigned male at birth who is attracted to men). The group was really interested in the idea of new labels coming from inside the LGBTQ+ community, rather than only being imposed by (mainly cis male) medical professionals. Some of the young people embraced the possibility of creating their own labels and categories as a way to find new forms of self expression and develop new possibilities for gender and sexuality. This opened up a conversation about LGBTQ+ sexologists, like Ulrichs or Magnus Hirschfeld, and how many of them campaigned for rights and engaged in activism.

We then created our own “timelines” which illustrated when in our lives we have chosen our own labels, when have we been labelled, and which labels we need to express ourselves.

Later, we were joined by the wonderful Cheryl Morgan, a historian and writer specialising in trans history across time and place.

Speaker Cheryl Morgan

Cheryl’s talk looked at the way in which different communities across the world embrace a wide variety of gender and sexuality labels; however, as she showed us, these labels are very much dependent upon the local culture, with different associations and significances in each culture. Cheryl made the important point that, although we cannot always know how people from the past understood their gender, we can look at how they lived their lives. This means that we have thousands of years of evidence of gender diverse and gender non-conforming people across history and across the globe.

Ur-Nanshe, a Gala singer, Ancient Mesopotamia

This was followed by a session in which we explored two figures from history in detail and thought about how they might have identified and how we might understand them from our own perspectives today. The first was a character found in a work by the ancient Greek satirist Lucian, called Megillos or Megilla – the male and female versions of their name. In the text, which we read as a group, the character declares: “I was born a woman like the rest of you, but I have the mind and the desires and everything else of a man”. The group thought about what ancient labels or models the other characters in the story use to describe Megillos’ identity. In the text, Megillos is described as a “lesbian”, because they come from the island of Lesbos, but according to one character in the text “they say there are women […] in Lesbos, who look like men, and are unwilling to have sex with men, but only to have sex with women, as though they themselves were men”. This is the origin of our modern label “lesbian” for women who have relationships with women. We thought about what labels we might use today to describe Megillos and whether their story can be seen as part of lesbian, trans and/or queer history.

When it comes to thinking about Megillos as a trans man, some participants saw the Megillos story as affirming, noting how confident Megillos was about his identity, consistently rejecting the labels offered by the other characters, and insisting on being wholly male. Other participants, however, emphasized the potential of the text – written by a cis author – to be read as satirizing and mocking the figure of Megillos and their gender expression

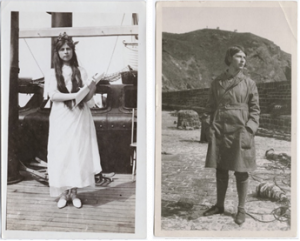

We also explored the life of the early-twentieth-century writer Bryher, who used the pronouns she/her, but also identified as a boy and chose a gender-neutral name. This led to a lively discussion about names, pseudonyms, pronouns, and authority.

Bryher was assigned female at birth and given the name Annie Winifred Ellerman, later taking on the name “Bryher” after one of the Scilly Islands, which they loved. We started by comparing photographs of Bryher from 1912 and 1921 and discussed the differences: the hair was shorter, the clothes were different and more gender neutral in the later photograph, their stance was more confident, and their facial expression more self-assured in the later photograph. We linked this change to Bryher meeting the poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and also embracing their identity as a boy, which is the term they preferred. Some of the participants pointed out that ‘boy’ was still used by some people today to signal trans masculinity rather than cis masculinity, and that wanting to be perceived as a boy rather than a man, could be really important.

The discussion ended with a conversation around whether Bryher can be categorised and regarded historically as lesbian OR trans; some of the young people agreed that it was not necessary to classify Bryher as one or the other, since they could also belong to the entire LGBTQ+ community. As such, both sessions introduced the idea that not all lives can be ‘neatly’ categorised as either trans or lesbian, especially in the past when such terms weren’t used in the same way they are used today.

Speaker Campbell X

We ended the day with a visit from Campbell X. Campbell is a filmmaker based in the UK and one of the leading creators of contemporary British Queer Cinema whose work often documents black LGBTQ+ culture. Campbell introduced clips from DES!RE, Stud Life, and Spectrum and later engaged in a fascinating Q&A session with Jason Barker. Campbell introduced important points about intersectionality re race and gender. He also pointed out that the ability to change and transform as an artist is often a white privilege because whiteness doesn’t register in the same way and isn’t often used as a label to categorise filmmakers and their work. Labels like ‘black filmmaker’ stay the same irrespective of the artists’ gender and/or sexual identity, which might change over time, and that becomes a marker of the filmmakers’ work and they are often used to tick a diversity box. Campbell also discussed the links between female masculinity and trans masculinity and the fact that gender nonconformity cuts across the LGBTQ+ spectrum, which resonated with some of the earlier discussions we had with the group about historical sources.